Packaging and distributing your Python code

Oregon State University

2025-01-29

Notebook to installable package

Hypothetical workflow for a researcher

- Work on idea for paper with collaborators

- Do exploratory analysis in scripts and Jupyter ecosystem

- As research progresses, need to write more-complicated functions and workflows

- Code begins to sprawl across multiple directories

- Software dependencies begin to become more complicated

- The code “works on my machine”, but what about your collaborators?

People heroically press forward, but this is painful, and not reusable

Imagine you start with a Jupyter notebook that looks like this:

import numpy as np

from scipy.optimize import minimize

# Rosenbrock function

def rosen(x):

"""The Rosenbrock function"""

return sum(100.0 * (x[1:] - x[:-1] ** 2.0) ** 2.0 + (1 - x[:-1]) ** 2.0)

def rosen_der(x):

"""Gradient of the Rosenbrock function"""

xm = x[1:-1]

xm_m1 = x[:-2]

xm_p1 = x[2:]

der = np.zeros_like(x)

der[1:-1] = 200 * (xm - xm_m1**2) - 400 * (xm_p1 - xm**2) * xm - 2 * (1 - xm)

der[0] = -400 * x[0] * (x[1] - x[0] ** 2) - 2 * (1 - x[0])

der[-1] = 200 * (x[-1] - x[-2] ** 2)

return der

# Minimization of the Rosenbrock function with some initial guess

x0 = np.array([1.3, 0.7, 0.8, 1.9, 1.2])

result = minimize(rosen, x0, method="BFGS", jac=rosen_der, options={"disp": True})

optimized_params = result.x

print(optimized_params)Reusable science, step by step

We can convert our notebook code into a simple importable module an and example calling it:

Reusable science, step by step

# example.py

import sys

from pathlib import Path

import numpy as np

from scipy.optimize import minimize

# Make ./code/utils.py visible to sys.path

# sys.path position 1 should be after cwd and before activated virtual environment

sys.path.insert(1, str(Path().cwd() / "code"))

from utils import rosen, rosen_der

x0 = np.array([1.3, 0.7, 0.8, 1.9, 1.2])

result = minimize(rosen, x0, method="BFGS", jac=rosen_der, options={"disp": True})

optimized_params = result.x

print(optimized_params)Reusable science, step by step

- This is already better than having everything in a single massive file!

- However, now things are tied to this relative path on your computer:

and are brittle to refactoring and change; plus, not very portable to others.

- But we can do better!

Fundamentals

What is a Python package?

First, let’s define module.

What is a Python package?

Deconstructing that definition:

- When I write

import modulenameI am loading a module - But we also talk about “importing a package”! This seems to imply a package is a kind of module.

- The module can contain “arbitrary Python objects”, which could include other modules.

- It’s almost like we need a special name for a “module that can contain other modules”…

- When loading a module, its name gets added to the namespace, a collection of currently defined names and objects they reference:

numpy.random.default_rng

Aside: why does Python have modules?

Because it’s good for your code to be modular.

Where do modules come from?

- The standard library

- Python code

- Compiled C code

- A local file that ends in `.py (confusingly, also called a “module”)

- Third-party libraries that you

pip installorconda install(i.e., packages) - A local package

What is a Python package?

We spent all that time defining module, now we can define package:

- package

- A Python module which can contain submodules or recursively, subpackages.

“Package” can have multiple meanings!

- import package: the one we talked about, when you write

import packagename. We’ll start by making this. - distribution package: the actual artifact that gets downloaded off the internet and stored somewhere, like when you run

pip install package. We’ll make these too.

When should I turn my code into a package?

Two common cases for research code:

- Code that goes with a research article; mainly used to reproduce the results, AKA a (computational) project or a research compendium.

- A generalized tool or library that other researchers can use

Not all packages intended to reproduce a paper’s results need the full infrastructure we will discuss (documentation website, continuous integration, etc.).

Packaging your code

Next steps: packaging your code

- The goal is for your code to be installable, and distributable.

- Per the Zen of Python, this should be straightforward, right?

Next steps: packaging your code

Unfortunately, not so much. 😔

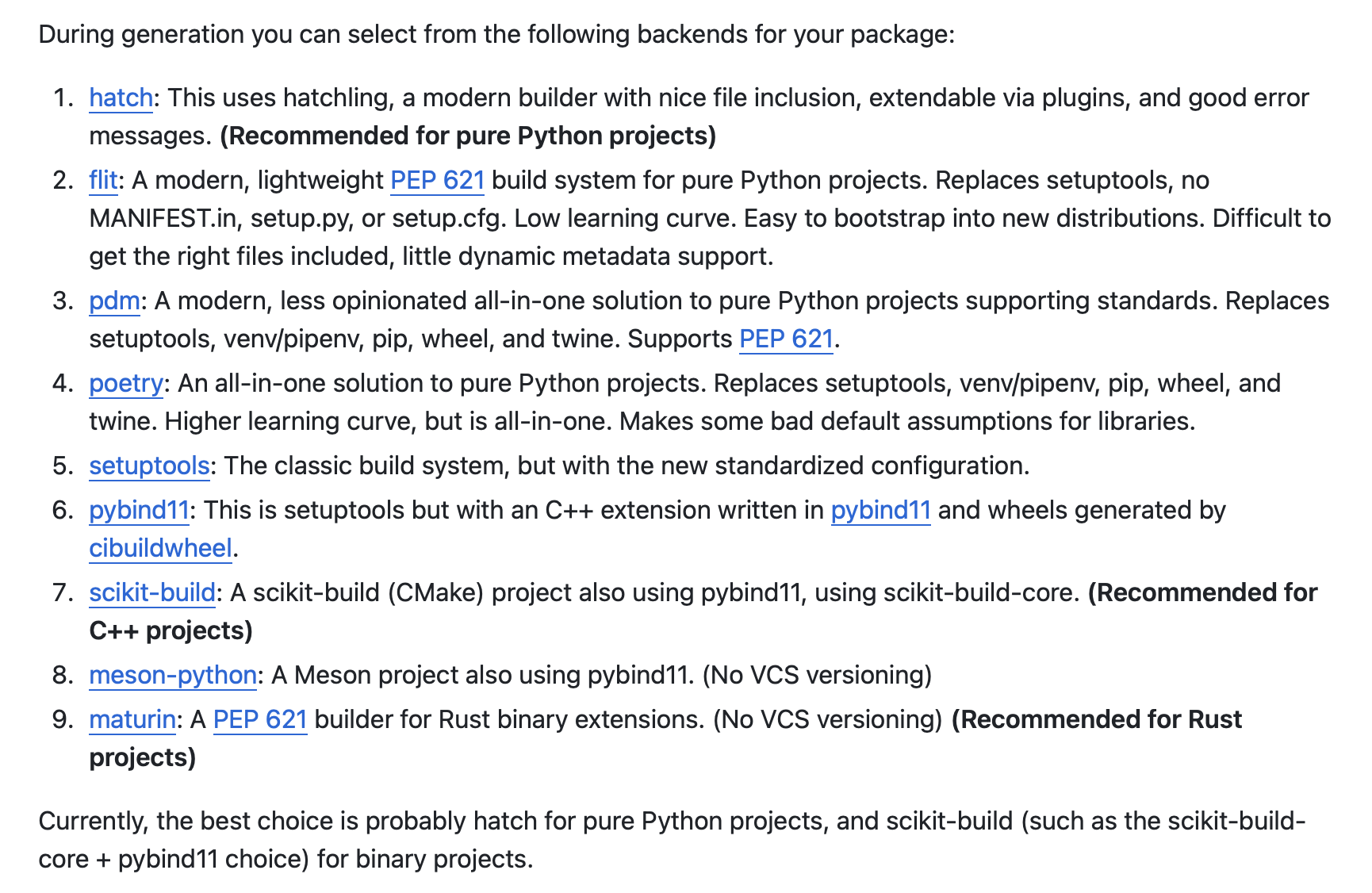

You might be asking: Why is there more than one thing?

Next steps: packaging your code

The good news: Python packaging has improved dramatically in the last 5 years

- It has never been easier to just point your package manager to some code locally, or on the internet, and get working Python code installed and running on your machine regardless of operating system or architecture

- This is a small miracle!

The bad news: Python packaging has expanded dramatically in the last 5 years

- By creating standards the PyPA allowed for an ecosystem of packaging backends to be created to tackle various problems (this is good!)

- This means that our The Zen of Python expectations are violated and we need to make design choices (hard for beginners)

Next steps: packaging your code

The okay news: You can probably default to the simplest thing.

- pure Python: Probably

hatch - compiled extensions: Probably

setuptools+pybind11orscikit-build-core+pybind11

Simple packaging example

Modern PEP 518 compliant build backends just need a single file: pyproject.toml

Simple packaging example: pyproject.toml

What is .toml?

“TOML aims to be a minimal configuration file format that’s easy to read due to obvious semantics. TOML is designed to map unambiguously to a hash table. TOML should be easy to parse into data structures in a wide variety of languages.” — https://toml.io/ (emphasis mine)

In recent years TOML has seen a rise in popularity for configuration files and lock files. Things that need to be easy to read (humans) and easy to parse (machines).

Simple packaging example: pyproject.toml

Defining how your project should get built:

Simple packaging example: pyproject.toml

Defining project metadata and requirements/dependencies:

[project]

name = "rosen"

dynamic = ["version"]

description = "Example package for demonstration"

readme = "README.md"

license = { text = "BSD-3-Clause" } # SPDX short identifier

authors = [

{ name = "Kyle Niemeyer", email = "kyle.niemeyer@oregonstate.edu" },

]

requires-python = ">=3.8"

dependencies = [

"scipy>=1.6.0",

"numpy", # compatible versions controlled through scipy

]

...Simple packaging example: pyproject.toml

Configuring tooling options and interactions with other tools:

Simple packaging example: Installing your code

You can now locally install your package into your Python virtual environment!

$ cd simple_packaging

$ pip install --upgrade pip wheel

$ pip install .

Successfully built rosen

Installing collected packages: rosen

Successfully installed rosen-0.0.2.dev1

$ pip show rosen

Name: rosen

Version: 0.0.2.dev1

Summary: Example package for demonstration

Home-page: https://github.com/SoftwareDevEngResearch/packaging-examples

Author:

Author-email: Kyle Niemeyer <kyle.niemeyer@oregonstate.edu>

License: BSD-3-Clause

Location: ***/.venv/lib/python3.13/site-packages

Requires: numpy, scipy

Required-by: Simple packaging example: Installing your code

and use it anywhere

# example.py

import numpy as np

from scipy.optimize import minimize

# We can now import our code

from rosen.example import rosen, rosen_der

x0 = np.array([1.3, 0.7, 0.8, 1.9, 1.2])

result = minimize(rosen, x0, method="BFGS",

jac=rosen_der, options={"disp": True})

optimized_params = result.x

# array([1.00000004, 1.0000001 , 1.00000021, 1.00000044, 1.00000092])Packaging doesn’t slow down development

PEP 518 compliant build backends allow for “editable installs”

Editable installs add the files in the development directory to Python’s import path. (Only need to re-installation if you change the project metadata.)

Can develop your code under src/ and have immediate access to it.

Packaging compiled extensions

With modern packaging infrastructure, packaging compiled extensions requires small extra work!

Packaging compiled extensions

In pyproject.toml:

Swap build system to scikit-build-core + pybind11

Packaging compiled extensions

# Specify CMake version and project language

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.15...3.30)

project(${SKBUILD_PROJECT_NAME} LANGUAGES CXX)

# Setup pybind11

set(PYBIND11_FINDPYTHON ON)

find_package(pybind11 CONFIG REQUIRED)

# Add the pybind11 module to build targets

pybind11_add_module(basic_math MODULE src/basic_math.cpp)

install(TARGETS basic_math DESTINATION ${SKBUILD_PROJECT_NAME})Packaging compiled extensions

src/basic_math.cpp:

Packaging compiled extensions: Installing

Installing locally is the same as for the pure-Python example:

Module name is that given in C++:

Distributing packages

Going further: Distributing packages

If your code is publicly available on the WWW in a Git repository, you’ve already done a version of distribution!

Going further: Distributing packages

Ideally, we’d prefer a more organized approach: distribution through a package index.

First, we need to create distributions of our packaged code.

Distributions that pip can install:

- source distribution (sdist): A tarfile (

.tar.gz) of the source files of our package (subset of all the files in the repository) - wheel: A zipfile (

.whl) of the file system structure and package metadata with any dependencies prebuilt. No arbitrary code execution, only decompressing and copying of files

Going further: Distributing packages

To create these distributions from source code, rely on our package build backend (e.g., hatchling) and build frontend tool like build

$ pip install --upgrade build

$ python -m build .

* Creating venv isolated environment...

* Installing packages in isolated environment... (hatch-vcs>=0.3.0, hatchling>=1.13.0)

* Getting build dependencies for sdist...

* Building sdist...

* Building wheel from sdist

* Creating venv isolated environment...

* Installing packages in isolated environment... (hatch-vcs>=0.3.0, hatchling>=1.13.0)

* Getting build dependencies for wheel...

* Building wheel...

Successfully built rosen-0.0.1.tar.gz and rosen-0.0.1-py3-none-any.whl

$ ls dist

rosen-0.0.1-py3-none-any.whl rosen-0.0.1.tar.gzGoing further: Distributing packages

We can now securely upload the distributions under ./dist/ to any package index that understands how to use them.

The most common is the Python Package Index (PyPI), which serves as the default package index for pip.

Distributing packages: conda-forge

The conda family of package managers (conda, mamba, micromamba, pixi) take an alternative approach from pip.

Instead of installing Python packages, they act as general purpose package managers and install all dependencies (including Python) as OS and architecture specific built binaries (.conda files — zipfile containing compressed tar files) hosted on conda-forge.

This allows an additional level of runtime environment specification not possible with just pip, though getting environment solves right can become more complicated.

Distributing packages: conda-forge

Popular in scientific computing as arbitrary binaries can be hosted, including compilers (e.g., gcc, Fortran) and even the full NVIDIA CUDA stack!

With the change to full binaries only this also requires that specification of the environment being installed is important.

With sdists and wheels, if there is no compatible wheel available, pip will automatically fall back to trying to locally build from the sdist. Can’t do that if there is no matching .conda binary!

Versioning

Semantic Versioning

Given a version number MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH, increment the:

MAJORversion when you make incompatible API changes,MINORversion when you add functionality in a backwards-compatible manner, andPATCHversion when you make backwards-compatible bug fixes.

To start: initial development release starts at 0.0.1, and increment minor version for subsequent releases.

Versioning with hatch & git

We actually already set up our hatch build system to automatically version our package based on git:

This tells hatch to look at the latest git tag and use that as the version number, stored in the automatically generated file src/rosen/_version.py.

Versioning with hatch & git

To document a new version, simply create a new git tag:

This will automatically update the version number in src/rosen/_version.py when next building the package.

Good idea: keep a CHANGELOG

Use a CHANGELOG file to document changes in your package over time.

# Changelog

All notable changes to this project will be documented in this file.

The format is based on [Keep a Changelog](http://keepachangelog.com/en/1.0.0/)

and this project adheres to [Semantic Versioning](http://semver.org/spec/v2.0.0.html).

## [Unreleased]

## [0.0.2] - 2014-07-10

### Added

- Explanation of the recommended reverse chronological release ordering.

## 0.0.1 - 2014-05-31

### Added

- This CHANGELOG file to hopefully serve as an evolving example of a

standardized open source project CHANGELOG.

- CNAME file to enable GitHub Pages custom domain

- README now contains answers to common questions about CHANGELOGs

- Good examples and basic guidelines, including proper date formatting.

- Counter-examples: "What makes unicorns cry?"

[Unreleased]: https://github.com/olivierlacan/keep-a-changelog/compare/v0.0.2...HEAD

[0.0.2]: https://github.com/olivierlacan/keep-a-changelog/compare/v0.0.1...v0.0.2Takeaways

- Packaging your code is a good idea

- Packaging and distributing your code is pretty easy

- Later, we’ll see how continuous integration can help automate this process